Civil War vanished immortalized in art, art galleries in Lebanon

Date: Thursday, April 17, 2014

By: India Stoughton

Source: The Daily Star

BEIRUT:

A total of 17,000 people are estimated to have disappeared over the

course of Lebanon’s 15-year Civil War. Close to 25 years after the

conflict was declared at an end, relatives of Lebanon’s missing are

still waiting for answers, many of them reluctant to follow the state’s

advice and declare their loved ones legally dead. In 1992, with the war

winding its slow way to a close and the families of those who vanished

during the conflict hoping desperately for news, multimedia artist Salah Saouli decided to tackle what had already become a taboo issue in a three-part installation entitled “Time Out.”

The artist, who works between Beirut and Berlin, where he has lived for roughly 30 years, contacted the relatives of missing individuals, listened to their stories and gathered photographs of some of the thousands of young men whose fate remains unknown.

“I worked on this project for two years and produced three main big works, three different installations,” the artist recalls. “When I first did it, I worked for a long time and then after six months I gave up. It was so difficult, especially because in ’92 it was still very [current]. The relatives of the people were thinking they’re still alive.

“I stopped for two months and then I thought: ‘No. I mustn’t give up. I have to find a solution.’ I began to think: ‘How can I make artworks that are visually very light and very attractive and calm, and then later you begin to think about the work?’”

For one of the trio of installations, Saouli gathered 23 portraits of missing young men, all of whom were staring directly into the camera. He printed two copies of each photograph, layering them atop one another with a millimeter of displacement, so that when viewed head on they appear still, but from an angle they seem to be moving, shifting in and out of focus.

He mounted the portraits in light boxes and hung them in a small room, which viewers entered through a single door. “You have them all around,” he says, “and when you go inside, you are converted to the object, because they’re all looking at you.”

This work, which carries a huge emotional impact for Lebanese audiences, was staged in Berlin in the early 1990s. Two decades later, a fraction of the work is on show in Lebanon for the first time. Three of the 23 portraits in “Time Out” form part of the semi-retrospective of Saouli’s work currently on show at Hamra’s Agial Art Gallery.

The show is comprised of installations on loan from the private collection of the Y. Hayek Foundation, which is organizing a series of solo exhibitions around the world to showcase the work of the contemporary Arab artists in their collection, placing it in a wider art historical context.

Saouli’s solo show consists of fragments and photographs of 13 installation works completed over the past 25 years, 10 of which form part of the Y. Hayek collection. The artist chose to exhibit three additional works, which he says help to round out the show and provide a comprehensive overview of his output.

Like “Time Out,” many of the works in Saouli’s show are closely tied to Lebanon’s history, to war, collective trauma and to memory. Others are showcased alongside the famous works from the Western art historical canon from which they take their inspiration, and focus on more universal struggles.

“I don’t see the difference because I work on a lot of things,” says Saouli, looking from a reduced version of his installation “The Days of the Blue Bat,” exploring memories of the 1958 crisis in Lebanon and subsequent U.S. military intervention, to photographs of “Composition for Mondrian,” an abstract outdoor installation dwelling on the threat posed to nature by urbanization and modernization.

“We’re suffering because of the [lack of] awareness about the environment. This is also a war but in a different way. The other pieces have a more direct story and this is a little but less direct but it’s all the things that disturb me, the things that I think about all the time.”

Many of the works on show have never been exhibited in Lebanon. Saouli wanted to exhibit “Time Out” at a gallery in Verdun in 1996, he recalls, but the venue refused to show the work, claiming people wanted to forget the war. While several of the works reproduced in part or captured in photographs in this exhibition were originally site-specific, many have a resonance in Lebanon that may have been lacking elsewhere.

Unfortunately, the diminutive size of the Hamra gallery has necessitated that Saouli present severely constrained portions of the original works on show, but – with the help of two false walls – the artist has succeeded in balancing the work in the limited space available.

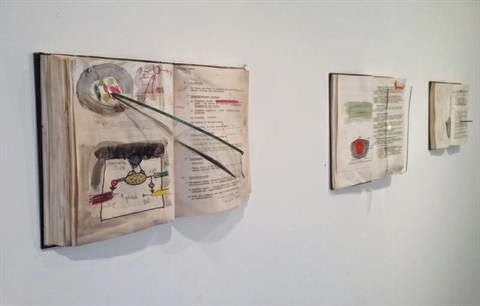

Beside “Time Out,” the oldest work on show, are three books from the “Interrogation” series, part of a trio of installations entitled “Best Seller,” which Saouli staged in Beirut in 2000 as part of Ashkal Alwan’s “Hamra Project.” The flimsy pages of medical books, packed with dense text, have been pierced from within by jagged fragments of glass that jut menacing toward the viewer.

Echoes of this juxtaposition of delicacy and violence run throughout the show. In the 1996 “Soundbarrier,” fragile Plexiglass sheets hang from lengths of fishing line. Each thin sheet, on which a fighter jet has been printed, sways gently in the wafts of air caused by the movements of passing visitors. Below them, a circular pile of glass rectangles, many smashes into glittering, lethal fragments, ties the ethereal work to the weight of the destruction below.

The men’s blazers hung above Agial’s staircase, next to Rene Magritte’s “Golconda,” the famous 1953 work capturing men in overcoats and bowler hats falling from the sky, form part of “Con-fusion,” an installation originally staged in a ruined Gothic church in Berlin. Agial’s staircase doesn’t provide quite the same soaring effect, but it does at least offer viewers the chance to crane their necks upwards from a precarious perch halfway up the stairs, should they so wish.

“I was very careful to put things in a very reduced form but still with flair,” Saouli says, “and with the presentation well done ... The relationship to the space is very important.”

While some viewers may experience a sense of frustrated yearning to see the works as originally conceived, the exhibition provides a valuable opportunity for locals to get a feel for Saouli’s work. As with most installation pieces, however, the physical interaction between viewer and artwork forms a crucial facet to many of Saouli’s works, which is missing from the cramped show.

“I try to put the observer in a special position so that they can think about the works in a semi-interactive way,” Saouli says. “You perform a physical action without thinking and then later you begin to think ... When it works it’s really very effective. Turn on the TV today and you see a lot of horrible images, so you shut it down. It's sometimes very important to find a special [perspective], to find something new, [which] let’s people go further and then think about it.”

“The Collection of Y. Hayek: Series 1, works by Salah Saouli” is up at Agial Art Gallery in Hamra until April 22. For more information please call 01-345-213.

For more articles, visit www.tourism-lebanon.com

The artist, who works between Beirut and Berlin, where he has lived for roughly 30 years, contacted the relatives of missing individuals, listened to their stories and gathered photographs of some of the thousands of young men whose fate remains unknown.

“I worked on this project for two years and produced three main big works, three different installations,” the artist recalls. “When I first did it, I worked for a long time and then after six months I gave up. It was so difficult, especially because in ’92 it was still very [current]. The relatives of the people were thinking they’re still alive.

“I stopped for two months and then I thought: ‘No. I mustn’t give up. I have to find a solution.’ I began to think: ‘How can I make artworks that are visually very light and very attractive and calm, and then later you begin to think about the work?’”

For one of the trio of installations, Saouli gathered 23 portraits of missing young men, all of whom were staring directly into the camera. He printed two copies of each photograph, layering them atop one another with a millimeter of displacement, so that when viewed head on they appear still, but from an angle they seem to be moving, shifting in and out of focus.

He mounted the portraits in light boxes and hung them in a small room, which viewers entered through a single door. “You have them all around,” he says, “and when you go inside, you are converted to the object, because they’re all looking at you.”

This work, which carries a huge emotional impact for Lebanese audiences, was staged in Berlin in the early 1990s. Two decades later, a fraction of the work is on show in Lebanon for the first time. Three of the 23 portraits in “Time Out” form part of the semi-retrospective of Saouli’s work currently on show at Hamra’s Agial Art Gallery.

The show is comprised of installations on loan from the private collection of the Y. Hayek Foundation, which is organizing a series of solo exhibitions around the world to showcase the work of the contemporary Arab artists in their collection, placing it in a wider art historical context.

Saouli’s solo show consists of fragments and photographs of 13 installation works completed over the past 25 years, 10 of which form part of the Y. Hayek collection. The artist chose to exhibit three additional works, which he says help to round out the show and provide a comprehensive overview of his output.

Like “Time Out,” many of the works in Saouli’s show are closely tied to Lebanon’s history, to war, collective trauma and to memory. Others are showcased alongside the famous works from the Western art historical canon from which they take their inspiration, and focus on more universal struggles.

“I don’t see the difference because I work on a lot of things,” says Saouli, looking from a reduced version of his installation “The Days of the Blue Bat,” exploring memories of the 1958 crisis in Lebanon and subsequent U.S. military intervention, to photographs of “Composition for Mondrian,” an abstract outdoor installation dwelling on the threat posed to nature by urbanization and modernization.

“We’re suffering because of the [lack of] awareness about the environment. This is also a war but in a different way. The other pieces have a more direct story and this is a little but less direct but it’s all the things that disturb me, the things that I think about all the time.”

Many of the works on show have never been exhibited in Lebanon. Saouli wanted to exhibit “Time Out” at a gallery in Verdun in 1996, he recalls, but the venue refused to show the work, claiming people wanted to forget the war. While several of the works reproduced in part or captured in photographs in this exhibition were originally site-specific, many have a resonance in Lebanon that may have been lacking elsewhere.

Unfortunately, the diminutive size of the Hamra gallery has necessitated that Saouli present severely constrained portions of the original works on show, but – with the help of two false walls – the artist has succeeded in balancing the work in the limited space available.

Beside “Time Out,” the oldest work on show, are three books from the “Interrogation” series, part of a trio of installations entitled “Best Seller,” which Saouli staged in Beirut in 2000 as part of Ashkal Alwan’s “Hamra Project.” The flimsy pages of medical books, packed with dense text, have been pierced from within by jagged fragments of glass that jut menacing toward the viewer.

Echoes of this juxtaposition of delicacy and violence run throughout the show. In the 1996 “Soundbarrier,” fragile Plexiglass sheets hang from lengths of fishing line. Each thin sheet, on which a fighter jet has been printed, sways gently in the wafts of air caused by the movements of passing visitors. Below them, a circular pile of glass rectangles, many smashes into glittering, lethal fragments, ties the ethereal work to the weight of the destruction below.

The men’s blazers hung above Agial’s staircase, next to Rene Magritte’s “Golconda,” the famous 1953 work capturing men in overcoats and bowler hats falling from the sky, form part of “Con-fusion,” an installation originally staged in a ruined Gothic church in Berlin. Agial’s staircase doesn’t provide quite the same soaring effect, but it does at least offer viewers the chance to crane their necks upwards from a precarious perch halfway up the stairs, should they so wish.

“I was very careful to put things in a very reduced form but still with flair,” Saouli says, “and with the presentation well done ... The relationship to the space is very important.”

While some viewers may experience a sense of frustrated yearning to see the works as originally conceived, the exhibition provides a valuable opportunity for locals to get a feel for Saouli’s work. As with most installation pieces, however, the physical interaction between viewer and artwork forms a crucial facet to many of Saouli’s works, which is missing from the cramped show.

“I try to put the observer in a special position so that they can think about the works in a semi-interactive way,” Saouli says. “You perform a physical action without thinking and then later you begin to think ... When it works it’s really very effective. Turn on the TV today and you see a lot of horrible images, so you shut it down. It's sometimes very important to find a special [perspective], to find something new, [which] let’s people go further and then think about it.”

“The Collection of Y. Hayek: Series 1, works by Salah Saouli” is up at Agial Art Gallery in Hamra until April 22. For more information please call 01-345-213.

For more articles, visit www.tourism-lebanon.com

Comments

Post a Comment